Brian Houghton Hodgson, the second of seven children, was born in Cheshire, in England, in 1800. Soon after his birth, his father managed to lose all his wealth thanks to an ill-advised investment and the family had to sell their house. His father was forced to take up menial jobs. At the age of 16, he was nominated by The East India Company’s director James Pattison and was admitted to Hailebury College to prepare for life as a civil servant in India. He graduated with a gold medal and a prize for his fluency in Bengali. He sailed to Calcutta, where he studied native languages and Indian law for a year at the College of Fort William.

Though dogged by ill health most of his life, he managed to master two languages: Persian and Sanskrit. At the end of his first year in India, he wrote: “My medical advisor recommended I throw up the service, and go home. ‘Here’, said he, ‘are your choices: six feet underground, resign the service, or get a hill-appointment.” To give up and return home was not an option as the financial burden of the entire family lay on his tired shoulders. To get a posting to the hills was almost impossible, but his credentials as well as well-meaning friends helped him with that. He got a posting in the hilly region of Kumaon, present day Uttarakhand, where his health improved steadily.

He was forbidden to leave his home in Kathmandu as he was a British resident. In 1822 he was promoted to the Foreign Office in Calcutta as acting Deputy-Secretary in the Persian department. But the following autumn he fell ill again and had to be sent back to the more salubrious climate of Kathmandu, where he stayed for the next twenty years. His first position was that of the postmaster, then he was promoted to the assistant resident before attaining the ultimate position of British resident to the court of the Ranas. Throughout this period he continued to suffer due to his ill health, which forced him to give up both meat and alcohol.

He missed his family and had only a few friends. So, he had to develop new interests and adopt new routines. Though he had no scientific training, he began to investigate the natural history of the area by sending out native collectors who brought him birds and animals. He amassed a large collection of birds and mammals skins, which he later donated to the British museum. These consisted of over ten thousand specimens and 1,241 sheets of written observations. He also discovered 39 species of mammals and as many as 124 new species of birds. Despite financial constraints, he maintained all of these at his own expense. Three artists, including the now-celebrated Nepalese artist Raj Man Singh drew the specimens with extreme accuracy under his careful supervision. Some he drew himself, including details such as breeding, colours and nesting habits. His first ornithological paper appeared in 1829, describing the huge Rufous-necked Hornbill, which inhabits the northeastern hill forests. Although he worked only from Kathmandu and later from Darjeeling, such was his thoroughness that few new birds have since been discovered in these areas. Many species of birds and many more races have been named in his honour, including Hodgson’s Frogmouth and Hodgson’s Redstart. He planned to write an illustrated book on the mammals and birds of Nepal, and even managed to find 350 subscribers, but nothing came of it.

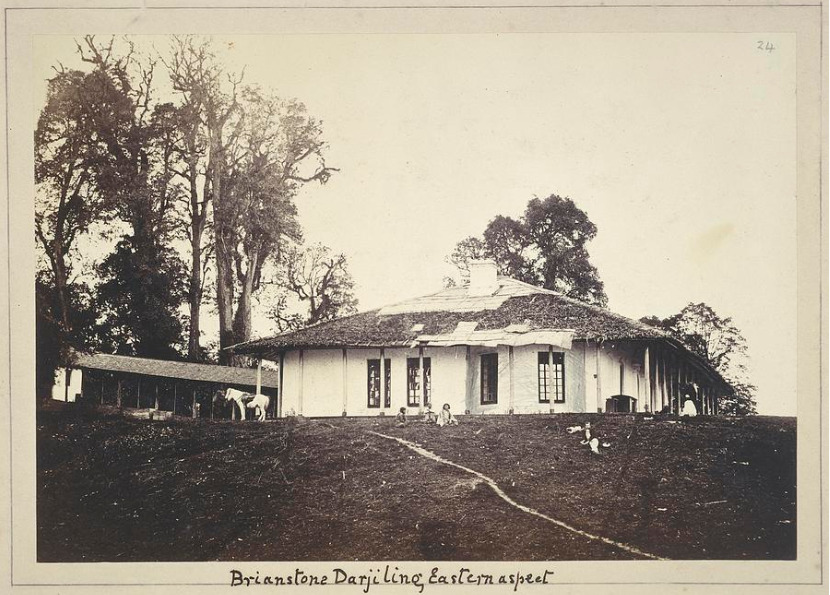

In 1844 Hodgson suddenly resigned from the service after being censured by the newly appointed governor-general Lord Ellenborough. When Hodgson returned to England, he was sympathetically received by the East India Company’s court of directors and enjoyed the long-awaited reunion with his surviving family, but he was unsuited for idleness. He decided to return to India the next year in order to continue his research in his personal capacity. From his new home in Darjeeling he spent the next thirteen years investigating, inter alia, the natural history of the region.

While on a short holiday to England and Holland, in 1853, he met and married Anne Scott, who returned to Darjeeling with him. Several years later, Mrs Hodgson’s health broke down and she sailed home to England, followed the next year by her husband and they settled in the Cotswolds. After her death in 1868, Hodgson married again, at the age of 69, and lived to celebrate his silver wedding anniversary.

Such was his reputation that A O Hume wrote “Hodgson combined much of Edward Blyth’s talent for classification with much of Thomas Caverhill Jerdon’s habit of persevering personal observation, and excelled the latter in literary gifts and minute and exact research. But with Hodgson ornithology was only a pastime or at best a parergon, and humble a branch of science as is ornithology, it is yet like all other branches a jealous mistress demanding an undivided allegiance; and hence with, I think, on the whole, higher qualifications, he exercised practically somewhat less influence on ornithological evolution than either of his great contemporaries….”

Hodgson passed away on May 23,

(The article was originally posted at Mumbai Mirror)

Leave a comment