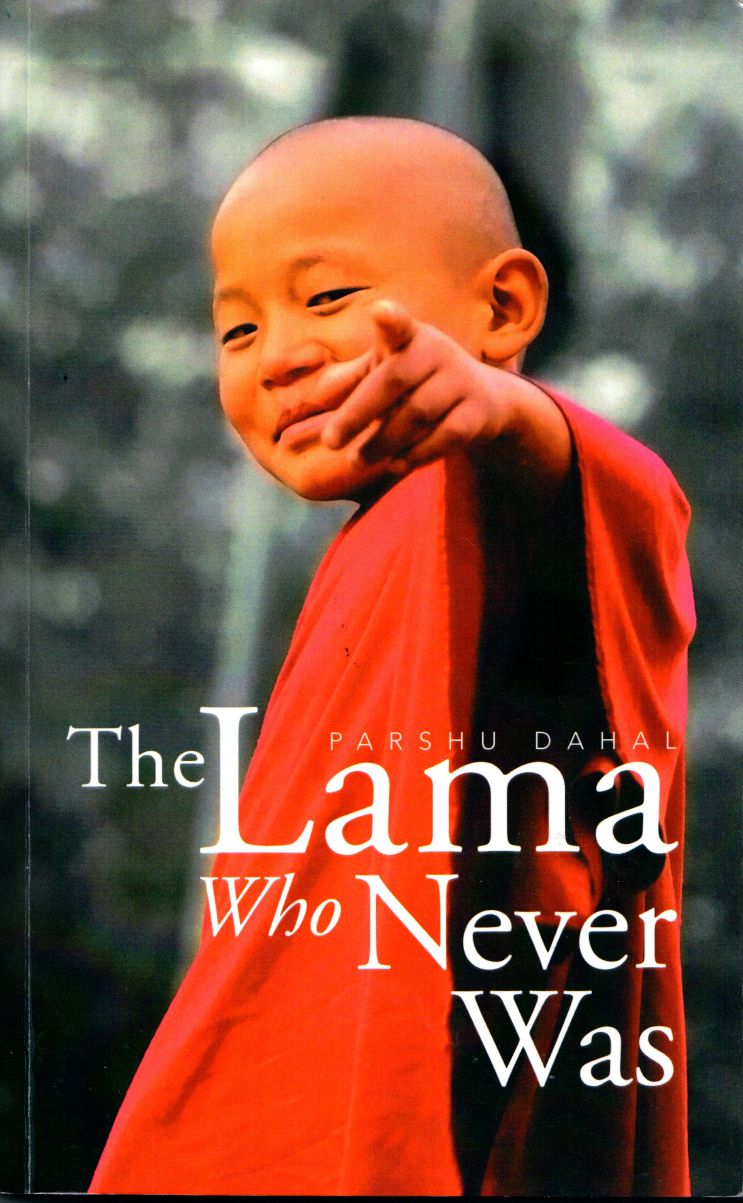

Parshu Dahal’s debut collection of short stories. 2017. Patridge Publishing

“A short-story writer should be brave. It’s a sad fact to acknowledge, but that’s the way it is” – Roberto Bolano, award-winning Chilean novelist.

There is a delightful sprouting of English writers from the Indian Gorkha community. Rich in heritage and society, we are all products of our background and writing has opened as the medium to share and enjoy. The fear of being technically unqualified to write has broken down, as finally, it’s the story, which matters, with quality language and rich creative writing skills. The same has been ventured by Parshu Dahal from Sikkim, a police officer by profession but with a creative mind to express in the written word.

Gorkhalis have always been excellent narrators. Whether an old lady or a young boy, they are born with extraordinary story-telling skills, but few have been penned down. Writers in the past had published a handful copies in the Nepali language with limited resources and reach. These books remain a mine of treasure to be republished. Coming out mainstream to write in English is a healthy movement heralding an emergence of literary narratives of the Indian Gorkha society. It is a wonderful way of our identity and literary prowess to get known by the non-Gorkhali society. Also, of course, a delight for Gorkhali readers because every story is identifiable with our experiences.

“Never” is an intriguing word. The book title, ‘The Lama who never was’ itself is a grabber. The back jacket of Dahal’s book described it as “Unpredictable”, “Spinning twists”, and “Social prejudices”– all true of the stories. I would like to add ‘touching’ and ‘poignant’ also. Though the sequence of stories could have been better juxtaposed. One almost loses it with the opening story ‘The Lame Squirrel’. The story is great but as first-place, not a great starter. ‘The Niece’ could have been a better appetiser.

All stories remain true to the back briefing, except the title story. The back cover describes it as “The Lama who never touched upon bed-wetting, a fairly common ailment amongst children that has a stigma attached to it”. However, on reading the story there is more to it. It is about children being given to Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, a common practice amongst the economically and socially limited hill families. Many hill children form the maximum human resource supply for a confined life of maintaining the ever-mushrooming citadels. The fact that adults take a decision for a child to be deposited for a lifelong commitment to the robe is questionable to the modern mind. Such a subject can be sensitive. Yet Dahal handles it with great courage and tact. Eight-year-old Jigmee is to be given to a Gangtok monastery. His mother’s feelings are described as such “She knows she is losing Jigmee forever, as he was being sacrificed to the monastery; every pious Buddhist family was expected to voluntarily offer a son to the institution for his nature and initiation for his nurture and initiation into Buddhist priesthood, the lama, to take forward the Buddhist legacy of the community. Little Jigmee is too young to comprehend the significance of it all.” Institutionalisation of children is a socio-economic compulsion and kudos to Dahal taking it on.

Dahal’s excellent story-writing skills reveal a strong sensitivity to the human mind and a keen eye for details. His words form pictures for the reader of actual presence in the surroundings or in the room. The Lame squirrel actually appears with Jetha Khaling. Feel the thrill of Maila Damai’s Narsingha and the climb. The stories feel as warning bells of time passing, a social culture diminishing. So grab the reads while you can still identify a phurloong, and if you do not, leave it to Dahal to expertly define it.

The slim book of 105 pages is suitable for Kindle or paperback. Would not recommend a hardback also on sale.

Awesome story