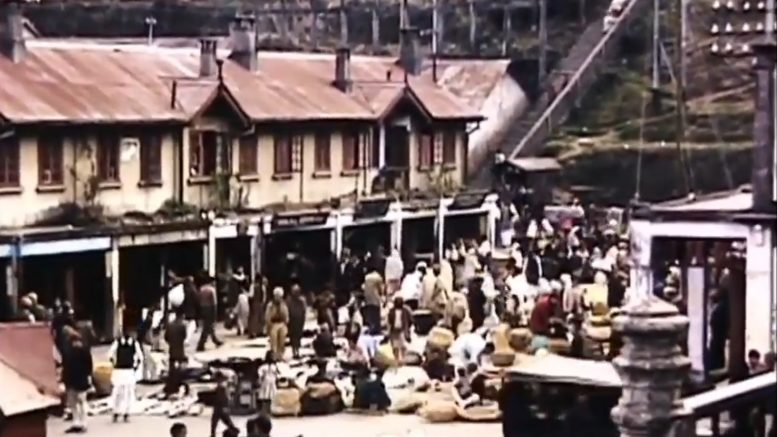

Kalimpong, a small non-descript town of just a few thousand inhabitants, because it was in the right place at the right time, was catapulted to world fame and riches in the early and mid 1900s, in the process becoming one of the most important and famous town of its size, in British India.

The proximity of Kalimpong to the Tibetan border (Tibet Autonomous Region-TAR) made it the most important entrepot to that country and the most significant trading hub of the region. Situated at one end of what was popularly known as the “Silk Route”, Kalimpong became the gateway to Tibet.

This so called “Silk Route” started at the bustling market of Kalimpong and wound its way through the narrow and treacherous mountain paths up the Chola Range and then through the wind-swept high altitude plains of the Tibetan plateau and ended up at Lhasa. This route crossed over into Tibet via the 14000 feet high Jelep-la Pass.

The other route, the one through Nathula, merged with the Jelepla route at a place named Phema, about 6km below Yatung in the Chumbi Valley. Yatung was earlier known as Shasima.

Although this route was famously known as “the Silk Route” the fact is that it was actually a Wool route. The Lhasa-Kalimpong trade route had nothing to do with Silk but the nomenclature of “Silk Route” still sticks to it. A small quantity of Silk did make its way to Kalimpong via this route but it in no way was the major commodity that was dealt in. The fact is that Silk Route was a term that was actually used for the network of routes that connected Central Asia and China to the Mediterranean countries through which a flourishing trade took place. These original Silk Routes started in about 130 BC when the then ruling Han Dynasty in China decided to expand its commercial links to the markets of West world. The problem was that beyond the western borders of present day Xinjiang lay a very harsh and treacherous expanse of desolate landscape inhabited by ferocious and barbaric nomadic tribes who were said to drink the blood of their victims and make clothing and bags out of their skin. This expanse of land had to be traversed by traders to reach the Mediterranean markets and hence first the Chinese rulers tried to appease the nomadic tribes by making them huge presents of rice, wine and textiles etc to buy peace. When this became too expensive the Hun rulers finally used brute military strength in forcing a safe passage through this land mass. In about 119 BC they managed to rid these routes from the perils of these nomadic tribes and their constant raids on the Chinese traders, thus opening the doors for the first safe and secure trans-continental road network.

This was the birth of the first Silk route. These trails and routes catered to the transportation of porcelain, perfumes, Silk etc, with Silk being the most valuable of all commodities. The importance of Silk in the ancient world was immense. Besides being utilized for its obvious use as a textile for clothing and bedding, it was also used along with coins as a form of currency. The Hun rulers are even reported to have used Silk alongside grains and coins to pay their troops. These trade routes actually came into being mainly for the trade of Silk, hence the name, Silk-Routes. However in present times all major trade routes that connect the trading centers in the Orient to other trading centers are referred to as Silk Routes, especially if these routes are lucrative ones.

The Silk Route through Kalimpong actually catered more to the import of Borax, Yak products, Gold dust, Musk but mostly Wool. Mule trains, sometimes in the hundreds, delivered wool to Kalimpong where it was weighed, sorted for quality and stored in huge godowns (locally called Unn Godams) and then was forwarded to Kolkata for export to England and elsewhere.

The journey time between Kalimpong and Lhasa generally took about three weeks. The mule trains or caravans that started from Kalimpong generally took two to three days to reach the Jelepla crossing Damsang, Pedong, Reshi, Rhenock, Lingtam, Lingtu and Kupup.

On crossing the Jelepla it entered the Chumbi Valley. Chumbi Valley was a richly cultivated valley and was one of the most prosperous regions of Tibet. The inhabitants of this valley generally controlled all the transportation required for the trade.

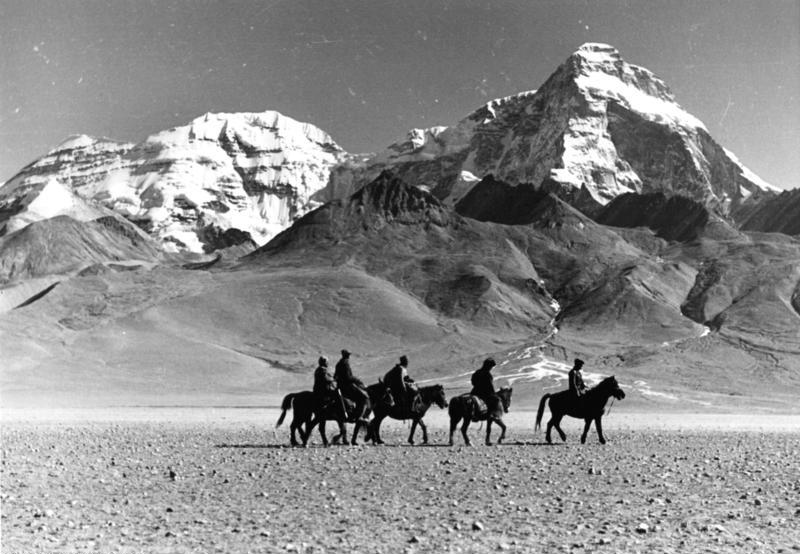

On the Tibetan side of the Jelepla, the small hamlet of Yatung existed. It was here that the first Trade Mart was established after the 1904 Younghusband expedition and the subsequent Treaty with Tibet. The Tibetans had earlier built a fortified wall all across the valley to prevent any outsider from crossing into Tibet. It generally took two days for a caravan to travel from Yatung to Phari which was a desolate, barren and extremely dirty hamlet situated on this trade route. From Phari it required about six days to reach Gyantse the third largest town in Tibet, after Lhasa and Singatse. From Gyantse it took about eleven days to reach Lhasa. Before reaching Lhasa, the traveler had to cross the Tsang Po River (River Brahamaputra in Tibet). This trade route was not for the faint hearted- this extremely difficult and hazardous journey tested the strongest of men.

The perilous paths leading up the Chola Range that had to be traversed were hardly two feet broad at places and one wrong step meant sure death. On the Tibetan high plains the extreme cold climate saw the temperature drop to minus 15 at times and the cold bone piercing winds were more than what most normal men could endure. In addition the constant threat of highway robbers and bandits always loomed large. An encounter with these bandits almost always left the traveler without any of their possessions including the very clothes on their body. The consequence of being-cloth less, food-less and shelter-less in the freezing cold and forsaken high plains of Tibet was a sure shot tryst with death.

Like all things, with the passage of time, this old Silk Route too has undergone dramatic change. The wheels of modernity have rolled many a circles over this Silk Route and now this erstwhile narrow dangerous mountain path is a proper metallic road. This Silk route or the Wool Route now can be called the Tourist Route with numerous tourist destinations dotting the route between Kalimpong and the Jelepla. The 120 km route from Kalimpong to the Jelepla offers a feast for the eyes as far as natural beauty is concerned. Several tourist spots like Pedong, Reshi, Lingtam, Juluk, Gnantang and Kupup on this route have become internationally recognized tourist destinations.

Of course Jelepla is now closed for the public, being under the control of the Indian Army who are eye ball to eye ball with their Chinese counterparts on this 14000 feet pass. As for that part of this Silk route that lies on the other side of Jelepla and which falls in the TAR (Tibetan Autonomous Region), it is said that now an ultra modern expressway connects it to Lhasa.

The two feet mountain tracks are now fifty feet wide roads, the mules and yaks are now the latest automobiles, the highway robbers are now the smartly dressed Chinese Police men, the three week journey is now a thirty hour one and the adventure and excitement now is replaced by just another uneventful and drab journey.

Thus ends the romantic story of the Silk Route that connected Lhasa to Kalimpong.

Be the first to comment on "Kalimpong and the Silk Route"