In December 2019 a cluster of pneumonia-like cases was reported in the Wuhan district of China for the first time. Five months later, this previously unknown contagious disease has wreaked havoc across the globe. The COVID19 aka SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2) pandemic has affected – directly and indirectly – almost every individual in the world. It has crashed entire economies, tested healthcare infrastructures, and caused havoc and general panic among the global public. The modern world has come to an uneasy and uncertain standstill.

With the global economy at an all-time low, the increasing pressure on supply chains and the large-scale unemployment, and food and supplies insecurities, there have been undercurrents of tension among nations. Although the UN secretary-general has called for a global ceasefire, the major UN member nations are yet to show agreement. The Chinese government has repeatedly been under fire by the US government for its inefficient handling of the pandemic. The Chinese government has also been accused of exporting below standard or defective PPEs to countries like Spain, Turkey and the Netherlands. Closer home, India is also involved in borderline conflicts with its neighbouring countries including Pakistan and Nepal. India is also engaged in a border standoff with the Chinese troops. The underlying tension between countries is a cause of concern in an already difficult time.

Moreover, there is a pandemic—more terrifying than the pandemics of disease—that has been, more often than not, inconspicuously tormenting humanity since time immemorial. That is the pandemic of hatred; it is the cascade of atrocities of xenophobia, domestic violence, social stigma, abuse, attacks, and discrimination. In times of crises, inequalities and injustices are exacerbated and that has been the case with COVID19.

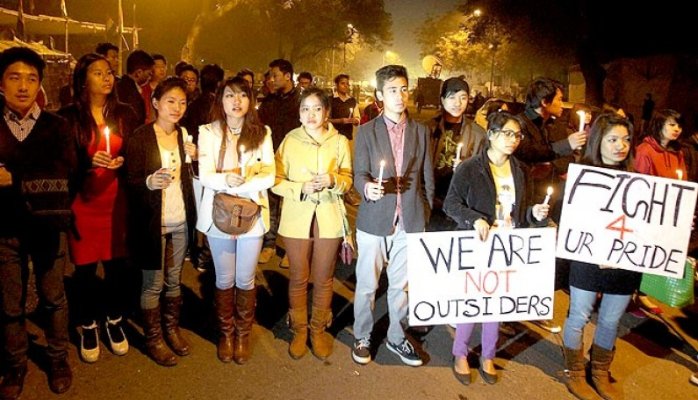

One such pertinent issue that also happens to be an incredibly sensitive one for the people of North-East India, among others is the issue of Xenophobia and rampant racism. If the situation for ethnic and racial minorities was inequitable pre-pandemic, it is only worse now. And this isn’t anything new. During the Black Plague, Jews were persecuted as carriers of the disease. In 1980 during the spread of HIV AIDS, the blame was on ‘outsiders’: the homosexuals, heroin addicts, Haitians and the hookers. More recently, in 2014, Africans faced stigma due to Ebola.

During the present pandemic, among the most hard-hit by xenophobia are the Asians. The virus tracing its origins back to China resulted in large scale stereotyping of Asians as potential virus-carriers and their consequent stigmatization. Although international organisations including the Human Rights Watch and the UN committee responsible for monitoring compliance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination have urged countries to take urgent steps and adopt action plans to prevent racist and xenophobic violence, the world has seen atrocity after atrocity being committed in the wake of the pandemic.

Global leaders, including the POTUS, Donald Trump, have been accused of propagating and instigating racial discrimination – directly and indirectly. Trump was also documented calling the COVID19 virus as the “Chinese virus”; it’s originating in China being the sturdy reasoning behind his comment. Chinese citizens and other Asians have faced abuse and attacks in the Americas, Europe, Africa and Asia as well. Chinese citizens have faced persecution in countries like Japan, South Korea and Indonesia.

In India, there has been a persistent drought when it comes to racial and ethnic tolerance. Islamophobia, homophobia, transphobia, antisemitism, and xenophobia are issues that we, as a country, have been dealing with. “Mainland” India has always held the North-East – perhaps due to its geographical location – an arm’s width apart. During the current pandemic, social media has risen to condemn and protest cases of racism in the country: a Manipuri girl was spat at and subjected to lewd comments, two young North-Eastern men were mercilessly maltreated by the police, North-Eastern students at prestigious institutes including DU and TISS, Mumbai faced discrimination during the pandemic. However, North-Easterns aren’t the only ones to suffer.

Mass gatherings of the Tablighi Jamaat and their subsequent travels to different parts of the country resulted in widespread islamophobia and stigmatization and discrimination against the Muslim population of the country. In cases of reverse-racism, North-Easterns have taken the position of the persecutor from being the persecuted.

In Darjeeling itself, the closely-knit local community has subtly been practising xenophobia. These are seen in avoidance of shops and establishments owned or managed by Muslims, the persecution of the Nepalese ‘bhariyas’ and the engagement in persistent rhetoric against mainland Indians.

While we have taken the words of our PM to heart and have been quite vocal about the local [atrocities] in the country, it is equally important that we are vocal about the global atrocities as a part of the global community. In the past week, in Minneapolis, a police officer was filmed kneeling on the neck of an African American man while he screamed, “I can’t breathe”. The victim was accused of loot and later died. At the crime scene, unaffectedly looking away was an Asian officer, a member of a race that is itself suffering racial discrimination and violence. But he is not the only one ignorantly looking away. There is a pandemic of hate in the world today and it is largely due to the fact that many turn a blind eye to it.

This wildfire of hate is fueled not solely by racism. Another pertinent issue in the world today is social stigma. News channels and other media have been continuously broadcasting news regarding violence against the front-line workers and discrimination and isolation of corona patients, healthcare workers, and support staff. The wildfire like a spread of misinformation has resulted in a widespread panic that has led people to stigmatize the patients and workers. There have been incidents of hurling of stones (in some cases, bricks) at health care workers and the security forces. There have also been complaints of isolation and unacceptance of recovered patients and workers on the break by society and neighbours for fear of the spread of the contagious disease.

Another stigma that is rocking the boat in an already turbulent sea is the stigma associated with menstruation. With the enforcement of lockdowns and the closure of schools and institutes, many girls and women – especially in rural parts of the world – face a shortage of both essentials for menstrual hygiene as well as the correct menstrual knowledge and information. Due to the limited access as well as the stigma associated with menstrual talk, young girls are often faced with doubts and hesitation regarding their bodies. They also often fall victims to abuse, molestation and danger when they are isolated from their families – in accordance with myths and rituals – during the course of their periods.

With a majority of females among the healthcare workers, menstrual stigma is also a problem on the frontlines. With a greater emphasis on PPEs and other pandemic essentials, menstrual essentials for these women have taken a back seat. Their long shifts, as well as the arduous and complicated procedure of changing into and out of the PPEs, is also a cause of concern for menstruating medical staff.

Well, periods don’t stop for pandemics; neither does rampant racism. And another thing that definitely doesn’t stop, is violence. Cases of violence have shown an increase in developed as well as third-world countries during the lockdowns. Domestic violence is another social evil that has been successfully eroding the pillars of social equality and justice. The National Commission for Women and Children in India has reported a maximum number of cases of domestic violence during the period of lockdown. While leaders and social workers urge the public to ‘stay safe, stay home’, for many women home is not a safe place. They face constant abuse (and this abuse need not just be physical, mind you) at the hands of their intimate family members. Violence arising from hate crimes is also a pertinent issue.

The world, our home is already afflicted with one of the most urgent global emergencies in its near history for it have to deal with any more crises. There is enough hate in the time of corona; what we need is a pandemic of love.

Writes: Snigdha Pradhan

Be the first to comment on "A Pandemic of Disease or a Pandemic of Hate?"