I am a mountain girl. Unapologetically so. I need to see my mountains to feel alive and to be alive. Which is why I could never work or grow roots in any place elsewhere. I need to wake up to the sight of the Kanchendzonga massif every day; on the days the skies veil her over, I know she is just there.

Despite the passage of years, there is this interminable, constant yearning, this hunger, this hankering to just see Kanchendzonga and to feel this entire gamut of emotions overrun and permeate my entire being. And to make me feel whole. There is, at once, the awe, the reassurance, the love, the veneration, the fierce pride, the anticipation, and the delicious thrill that just being able to gaze at my mountains has always evoked in me.

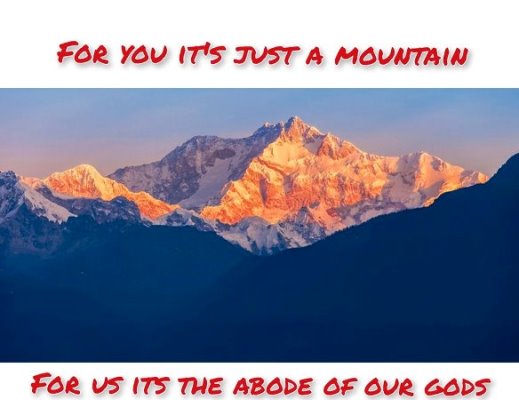

Kanchendzonga is not just a mountain. She is the embodiment of Sikkim. I subconsciously use a feminine reference as she is the nurturer. And yet Kanchendzonga is the bulwark; he protects us physically from the harshness of the cold winds from the higher climes and has served as a natural barrier against foreign aggression. Kanchendzonga is our mother and our father, our mountain god, the adobe of the deity, our past, our present, our future, and an intrinsic part of the Sikkimese psyche.

The Rong folk or the Lepchas believe that Itbu Debu Rum, the Mother Creator, created them from the purer than pure snow of Kongchen Chu. The Lhopos or the Bhutias venerate the mountain as the abode of their guardian deity, Kanchendzonga or Dzonga Taktse. Dzonga is an emanation of Namsey Dungmar or Kuvera of the Red Spear. Whether we venerate the mountain as the abode of the gods or the deities themselves, when one lives in the lap of this part of the Himalayas, our gods become our mountains and our mountains our gods. You don’t have to be Sikkimese to be entranced and enraptured with the mountain; it simply embraces you in its entirety, and you will never be the same again once you have walked in her shadows or been blinded by her brilliance. It is a love story like no other: with no beginning and with no end, with only the timelessness of just being.

With the recent opening up to mountaineering of our sacred peak, and other peaks, emotions are running high. The internet is awash with #SaveKanchendzonga. All the facts and figures are there for anyone interested to read: which peaks, what heights, the environmental challenges, the earlier expeditions, the summitting from the Nepal side, the comparisons with the graveyard of Everest. These are facts, and facts are cold. I wanted to attempt to articulate what our mountains mean to us in a more personal and intimate narrative.

Throughout our history, Sikkim has stood out like a sore thumb on the map of the world. Long considered an upstart aberration, our relatively smaller land endured raids and skirmishes with and by larger, more militant neighbouring Gurkhas and Bhutanese and Tibetans; China proposed the Five- Finger theory; India swallowed us. Bloodshed, intrigue, betrayal, shrinking geographical boundaries, politicial machinations, coronations, the advent of the British, Tibetan matrimonial alliances, a new national anthem, the rape and plunder of our rivers nurtured from her crown, Kanchendzonga has stoically witnessed it all. And continued to be the one unchanging entity that we could cling to and have faith in. She says nothing; she knows everything. The Custodian of our faith, our culture, our identity, our history just watches over us quietly, reassuringly.

Over a century ago, a young girl was walking in an aristocratic mansion in Lhasa, Tibet when she had a visitation. She described this being as being dressed in resplendent brocades with what looked like battle gear and armour and an aura so powerful she knew it was a higher being. It was the face that arrested her attention. She remembered vividly the fiery red countenance with the mystical third eye and the crown with five human skulls, she remembered the wrathful grimace, but she was unafraid. This entity addressed her and said: You are coming to my land, venerate me, I will protect you. The young girl was intrigued but thought no more of it.

In 1918, Kunzang Dechhen of the aristocratic Ragasha family of Lhasa was despatched to Sikkim, the chosen bride of Chogyal Tashi Namgyal of Sikkim. He selected her from her photograph which was sent to him, along with those of other potential brides. After many days of travel on harsh terrain, the new bride-to- be alighted from her horse at the Gangtok Palace, and among the first things that greeted her in her new country was a mask of the same entity that had visited her in her Lhasa home: Kanchendzonga. Recognising him immediately, she quickly prostrated before him, and needless to mention, all her life, the Maharani and later Gyalyum (Queen Mother) of Sikkim had an unflinching belief in and intrinsic connection with Kanchendzonga.

The Maharani was continually involved with Pang Lhabsol celebrations at the Tsuklakhang Royal Chapel. Pang Lhabsol is our Sikkimese festival that venerates Dzonga and other mountain deities and propitiates their blessings and protection for the land and its people. Contrary to popular belief, it lasts an entire month, usually in and around September, and culminates with the ‘cham’ or religious dances on the final day. Earlier the National Day of Sikkim, and with the chams suspended briefly in the capital, Pang Lhabsol has recently seen an impassioned renaissance in Gangtok with a new brace of Sikkimese youth stepping up to don, with pride, the ceremonial costumes of the Pangtoedpas or the Warriors of Dzonga and upholding an age- old tradition and, more importantly, giving a new generation a visual reintroduction to a vital aspect of their identity as Sikkimese : an immutable bond with and reverence for their mountains.

Meanwhile, in one quiet corner of the Tsuklakhang, veiled behind curtains, there lies a piece of Sikkimese history often dismissed as folklore by the naysayers and ignorant. In another time, during another tumultuous period of Sikkim’s history, another Sikkimese king and queen had to run away to a safer place. Which king, which queen? I do not particularly like spoonfeeding; the curious can read up on our history and find out. The 1908 History of Sikkim documents how a mask of Kanchendzonga fell into the lap of the fleeing queen, and she carried it with her.

Did Dzonga feel a particular connection with the Queens? In our history, it is not uncommon to find queens of sterner will than the Chogyals. Harking back to my current narrative, this selfsame mask found its way back home and rests quietly at the Royal Chapel. Our Sikkimese narrative has been dismissed as folklore by many, but even the purportedly mythical pillars that Jowo Khye Bumsa erected at the Sakya monastery do stand testimony to our collective history -predating the 1642 consecration of the first Denjong Chogyal- even today.

Has Kanchendzonga not been summitted? A tall mountaineer- find out his name yourself- once stopped short of the peak from the Sikkim side, but he still technically towered over the peak. From the Nepal side, Kanchendzonga has been conquered. Can we ‘save’ Kanchendzonga? The Central Government has displayed an undeniable finesse for lightning quick strikes and an ability to ride roughshod over all sentiments.

As usual, we were blindsided by the notification opening up our sacred mountain and sister peaks to the crampons of foreign dollar tourists. We have lost our country, our rivers have been raped and dammed and damned, our multiculturalism has been shredded into tiny schisms, our dignity and honour smote into the ground, our children’s and their children’s collective futures compromised before it even began, our politicians are tainted excrement… What else was there to lose? Only Kanchendzonga stood tall. From past experience, the mountain itself has resisted efforts to be conquered, wreathing itself within a cocoon of the most inhospitable weather for days of end to thwart man’s need to ‘conquer’. How long will our mountain protect itself?

Do our gods reside only on the summit? Does our faith and our connection to the mountain cease if it is summitted? Our faith has always been as expansive as the skies into which Kanchendzonga sometimes appears to smoke out puffs of clouds, but then again, Kanchendzonga is Sikkim. She is the only thing pristine left in Sikkim today. Will she be laid low? Are we going to be true to form and be the feckless, reactive people we are conditioned to be?

Writes: Tenzin C Tashi, a BTech and MBA degree holder, is also an established writer in her native state Sikkim. She worked as a Sikkim-centric researcher and editor at the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology for over a decade. She currently owns The Rilon Farm and grows organic strawberries. Views expressed are the author’s own

This article was originally published here.

totally support the view and apologias for any wrong done us(late but hope not too)). and appeal to each and human to come forward for the cause.