Now, who were the 8th Gurkha Rifles? Formed by the British in 1824 and transferred to the Indian Army in 1947, its Battle Honours upto WWII with two Victoria Crosses, one for Rifleman Lacchiman Gurung in Burma, run like this: Burma 1885-87; La Bassee, Festubert, Givenchy, Neauve Chapelle, Aubers, France and Flanders 1914-15; Egypt, Megiddo, Sharon, Palestine, Tigris, Kut-at-Amara, Baghdad, Mesopotamia 1916-18; Afghanistan 1919; Iraq 1941; North Africa 1940-43; The Gothic Line, Coriano, Sant’ Angelo, The Gaiana Crossing, Point 551, Italy 1942-44; Tamu Road, Bishenpur, Kanglatongbi, Mandalay, Myinmu Bridgehead, Singhu, Shandatgyi, Sittang, Imphal, Burma 1942-45.

This was how an illustrious Gorkha Regiment was reduced from its glorious past to shooting at unarmed people rooting for their rights to their language in the remote hills of Darjeeling. The movement required political pacifism, settlement through discussions and negotiations, at worst some simultaneous police action for maintaining some semblance of normalcy. But using the military as an option to deal with a civil disobedience movement was a drastic desperation and an alien reaction in a democratic society, as it was also an infringement on the honour of the historic infantry battalion in question.

While we expected Gorkha soldiers to appear in their camouflaged battle fatigues, words arrived in town that they had refused to obey the command to shoot at civilians in peacetime. Moreover, they were mostly Gorkha soldiers from Nepal and they wouldn’t shoot their Nepali blood brothers and sisters of Darjeeling. Period!

But this was treason. Disobedience warranted court martial en masse of the entire battalion. What would it be?

Presently, a fully equipped contingent of SRP in their ash-coloured shirts and khaki pants arrived in town, ready with their SLRs. It was amazing to see they were all Nepalis, two to three years older than me. They set their pace every 50 feet along the most sensitive sidewalks of the town’s streets, including the volatile Chowk Bazaar quadrangle.

By the next day, the Lebong Cantonment was empty of the 2/8GR. They had just faded away in the night; they just melted away from Darjeeling. How did they do it? Their long convoys didn’t pass through the town that had the only road leading out. Did they trek through Sikkim and reached the Teesta River Valley to peter out in the plains? Nobody knew about it. It was a stealthiest vanishing act of the Gorkhas. Soon the 3rd Punjab replaced them in Lebong and its band played Scottish airs on the Chowrasta Maidan on Sundays. Then we heard of the debacle of the 2/8GR, met at the hands of the Chinese PLA in the Indo-China War. Was it a rumour? Was it a message of a bitter memory not easily forgotten by somebody up there?

The language showdown came to pass, and the rest is history. This is just a record of a teenager who saw most of the tense days and nights in the 1960s.

Between then and now, the Nepali language has received its own signature in the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council where Nepali has become Gorkhali.

What, then, about the major crusaders involved in the great agitation? How did they fare in the Darjeeling of Gorkhaland? Were they honoured or ostracized and alienated by Gorkhaland?

Indra Sundas, the writer of the novel ‘Mangali’, was a senior magistrate in Darjeeling. But he chose to leave Darjeeling and spent his last years in the plains of Siliguri before he passed away in his mid-80s sometime ago.

Ganesh Lal Subba, the dapper law practitioner, is also no more.

Arsonists in the Gorkhaland disturbances destroyed Indra Bahadur Rai’s houses and farms. He now divides his time between Darjeeling, Siliguri and Calcutta and also likes to visit Kathmandu.

Til Bikram Nembang, the student leader from Nepal, now fully known as Bairagi Kainla, is back in Kathmandu. He has his own ‘bairag’ with the Nepali language in Nepal.

Others too paid heavy prices for their faith and belief in the Nepali language. Many casualties of the fight received neither reprieve from their sufferings nor appropriate succour while many exiled themselves from Darjeeling.

In a fitting retrospection, those who displayed their feelings and demonstrated their protest were branded anti-national by state apparatchiks. Government service holders, most especially, would be hounded and harassed indefinitely. Amber Gurung was thus a marked man, and what he did that day at Chowk Bazaar would pave his way to his exile in Kathmandu. Before that official swoop, he lost his job as creative chief at the Lok Manoranjan Shakha (Folk Entertainment Unit).

Dissent and protest had no place in the realms of one’s individual freedom and personal independence according to the official scheme of things in the Federal Democratic Republic of India at that time. There were always the unfriendliness and confrontational and adversarial possibilities at the state level. Everything the government did for you was a big favour. The top was very heavy on you. These were my feelings of fear and loathing in India when I lived there, in Darjeeling.

India may have been the biggest democracy in the world, but its methods were demonic in suppression and vendetta during those days. The state machinery of intelligence, vigilance and harassment would be Stalinist in approach and practice, carried out by the local police, the armed police, the paramilitary SRPF and the CRPF. The Intelligence Bureau (IB) had its DIB (District Intelligence Bureau) to watch over you. India was a police state of so many prying vices and scrutinising eyes. It was all spooky, suspicious, with fear psychosis reigning supreme in India of those days. That’s what I think of India during those years of Terror Raj in Darjeeling. This still holds true when retired generals continue to be appointed governors in insurgency-ridden states of India. To its own cowed citizens, India is an ever-ready menace, its multi-fanged military machine willing to make mincemeat of you.

These then are my own notations to what Ishwar Ballabh wrote about his own moments of truth during those turbulent times in Darjeeling, some 45 years ago.

[Concluded]

Originally published in The Kathmandu Post on Sunday, August 21, 2005

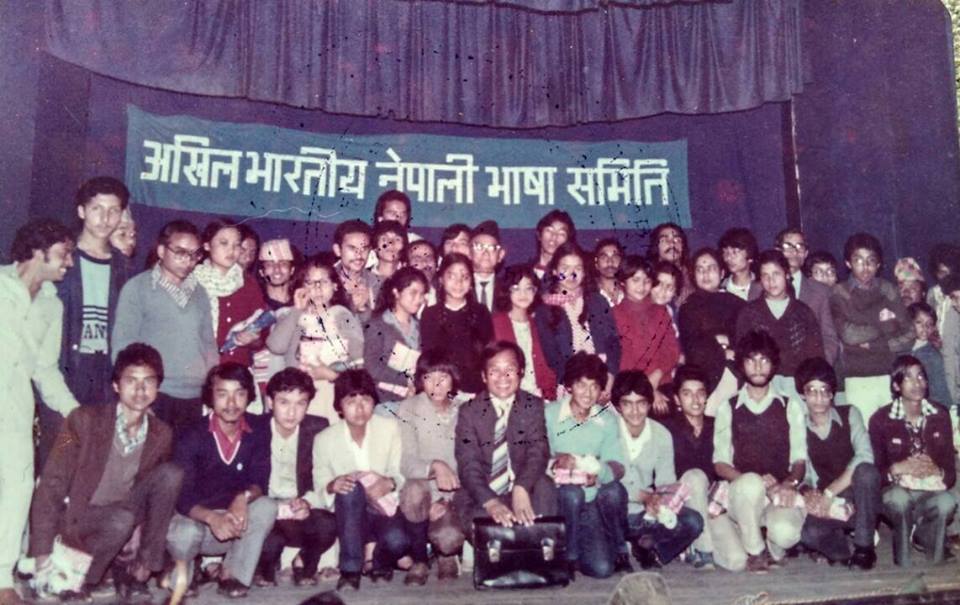

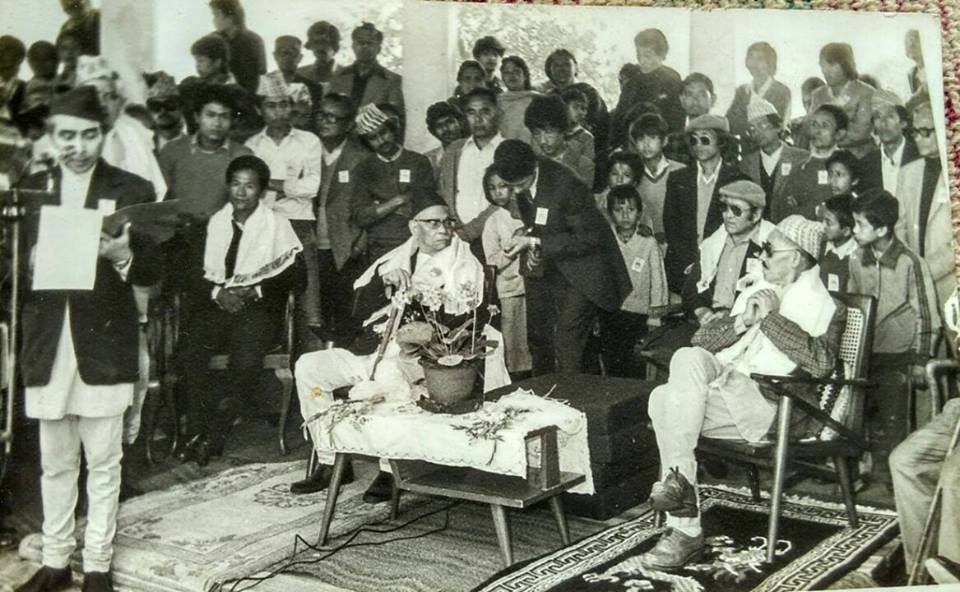

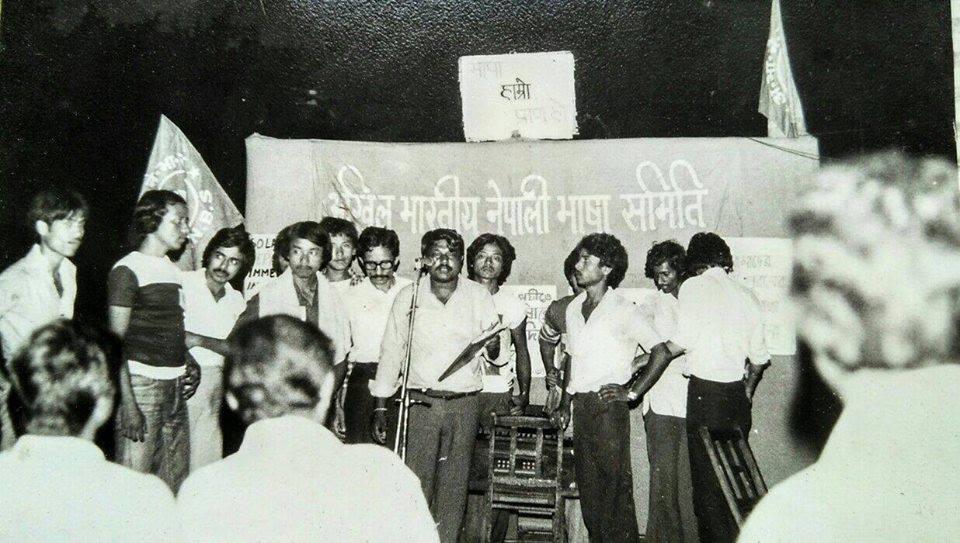

[All pics via: Lob Thami]

…………………………….

This is the 3rd and final part of a 3 part series on Nepali Bhasa Andolan, the 2nd part was published yesterday [you can read part 1 it here: https://bit.ly/2PktDLl and part 2 here: https://bit.ly/2PmRvOC] written by one of our eminent contemporary writers Mr Peter J Karthak. we request all of you to kindly SHARE these articles, so that it reaches all of our people, and make them aware of why conserving our language and heritage is so important. We THANK Mr Karthak for kindly permitting us to reproduce his work.

……………………

Author’s note: Some minor changes (additions and deletions) have been made in this edition for Darjeeling Times/Darjeeling Chronicle.

Writes: Peter J. Karthak

Kupondole, Patan, Kathmandu, Nepal

Tuesday, July 19, 2016

This piece was originally published in TheDC FB page on – August 22, 2016. We are republishing it to help our youths connect with our history.

Leave a comment