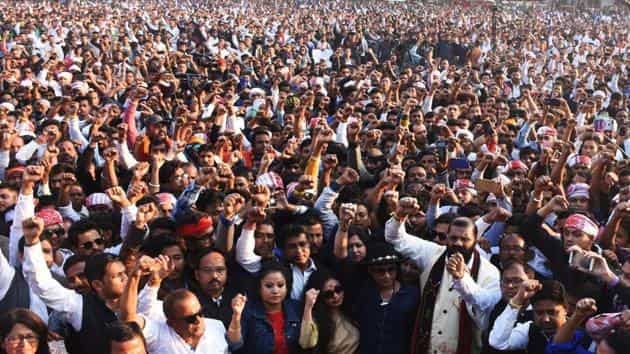

As the 2019 Lok Sabha Elections draw closer, media in the Northeast is abuzz with new stories every day; streets are overflowing with protests, and political parties are busy taking credits or blaming each other for the successes and failures of the past 5 years.

2014 was a game-changer for the country’s political landscape in many ways. BJP’s convincing win proved that the country has shed its Congress-centric governance and bureaucratic system. More importantly, it was the rise of Narendra Modi’s development-centric politics that sought to provide an alternative to the change-starved youngest democracy of the world.

The rise of Narendra Modi as the solution for India’s socio-economic problems also changed the political narrative of the NorthEast region, which traditionally shares very little of mainstream India’s political concerns or narrative. Since independence, politics in this region has mostly found itself aligning to the powers in Delhi. Very few had anticipated such an overwhelming response to Modi wave given to his affiliation with BJP. Today, the BJP is in power or coalition with almost every state, except for Mizoram.

However, the shift of power, one must remember, is not an ideological shift but a convenient arrangement for a promising future. And true to the promises of Modi’s development agenda, more people today have access to gas connections, electricity, better roads, than ever before. However, the recent protests against the government on the controversial CAB Bill, NRC issue of Assam, ILPs, and the reaction of the government against political dissent raises several questions as to what is it that the NorthEast wants?

Are the problems of Northeast just limited to economic concerns? Or is there something more than the economic aspect? Protests here, unlike the rest of the country, are very intense and sees wide participation from every section of the society. What is it that Delhi doesn’t understand about Northeast?

The Delhi Dilemma: Trivializing Local Issues over National Interest

Historically, the Northeast had never been emotionally integrated with the larger Indian union, and the region passed onto India’s hand because the British didn’t know anything else to do. By the time, the Japanese fighters crossed into India through the North-east, the region has already established itself as a strategic point for India’s security. It was that hot piece of bread the new Indian Union put in its mouth, but couldn’t chew because of the heat, nor could it spit out.

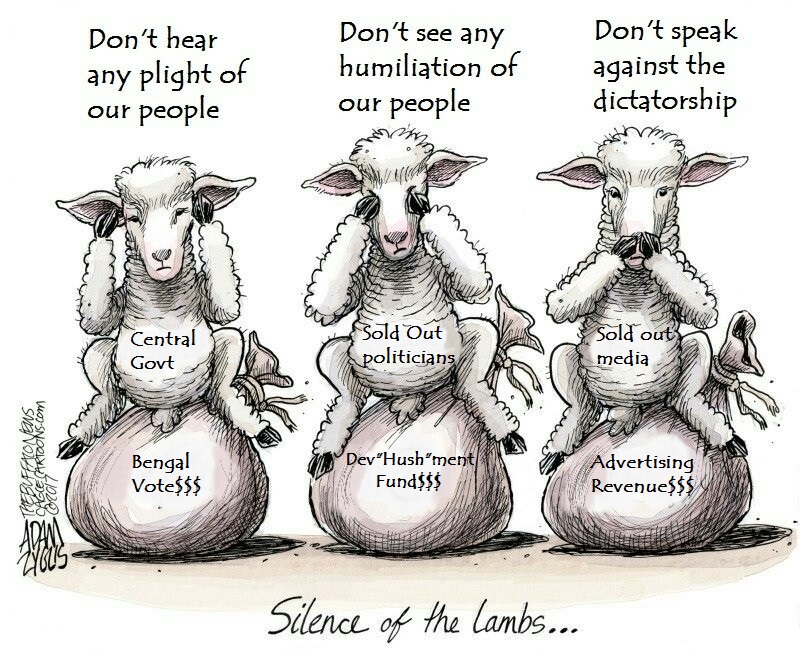

The new Indian bureaucracy, which simply took over the reins from the British didn’t have much idea about the region or its complex political dynamics. All decisions were made in Delhi and simply executed through the army in the region, most of the time without any understanding of the ground situation. Any political dissent was labelled an act of separatism and the army had a free hand to deal with dissent, both social and political.

The high-handedness of Indian bureaucracy and Delhi’s myopic views about the region pushed the region to a corner from where the only option to fight back was retaliation against India (symbolized by the army). Things have definitely changed over the past few decades, but the bureaucracy is still hung-over Delhi, for whom local concerns do not matter much in the wake of national priorities or interest.

Policy makers, seating in Delhi think that the problems of the North-east is purely economic. They are convinced that with development and economic progress, problems facing the region will simply vanish into thin air. Nothing can be further from the truth that such naivety. For the policymakers seating in Delhi, it is only the beautiful landscape, cultural uniqueness, and the hospitality of the people that stands out. No wonders, tourism is the most heavily promoted industry from the region and all ideas of economic prosperity woven around tourism.

Land and Belongingness: The Crux of the Issue

‘Land Rights’ and ‘Territorial Jurisdiction’ are perhaps the most important keywords that explain the underlying political current of the region. Be it the insurgency problems, ILP issue, CAB, NRC, anti-immigrant, citizenship, and every other US v/s THEM issue is a by-product of the land-rights related issues.

- Manipur: With over 40 different armed groups, the ‘fight for independence from occupation’ or to defend one’s community from external threats is a strongly territorial phenomenon. To this day, the insurgent groups are a huge stakeholder in the social, economic, and politics of everyday life in Manipur. The state holds the record for the longest highway blockade when the Naga and Meitei communities had their disagreements with regards to the territorial jurisdictions of each. The Nagas in Manipur were also engaged in a bloody civil war against the Kuki community during the 1990s because one community alleged the other one of encroaching upon their ancestral land. With three major stakeholders claiming territorial rights over the tiny state, the ‘land’ is an integral part of the ethnic identity and no amount of free gas connections, development projects, and free aids will stand in comparison when it is the question of the land.

- Nagaland: The Naga issue began with the idea that the ‘Naga people’ are different from India and have a unique history and culture. The ongoing Peace Process is part of Nagaland’s everyday socio-political narrative. Beginning with the bloody civil war waged by the NSCN and other Naga armed groups against India in the 1960s, the Naga freedom movement has been the torchbearer of all armed conflict in the region. Most other secessionist movements in the region owe their allegiance – ideologically, logistically, and arms supply. The effect of the movement is directly felt in the Naga-inhabited regions including Assam, Manipur, Arunachal, and even in Myanmar territories. Today there is peace in the Naga areas, only for the hope that the NSCN and Government of India are approaching a peaceful resolution to the long pending issue. Any threat to the peace process threatens to disturb the peace, not just in the Nagaland but across the Northeast region.

- Mizoram: The Mizo National Front in the 1960s, waged one of the bloodiest civil wars against India and seeking its own independence. The Indian Airforce carried out bombing across Mizoram to quell the uprising. While the Mizos dropped came forward for peace and reconciliation after the bombing, it went into a reclusive state trying to cope with the post-traumatic stress. In its isolation, it has emerged as one of the most forward thinking and peaceful state in India. However, the issue of land rights, fear against outsiders, and cultural issues have become ingrained in the psyche of the people. Mizoram is one place that doesn’t shy away from bringing up the secession topic as we recently witnessed in the protest against CAB Bill. Brus and Chakma refugee issues are already a huge political issue here.

- Tripura: Tripura is often cited as an example of what happens when migration is unchecked. The indigenous people, having outnumbered by migrant population, are today seeking greater autonomy and self-rule calling for statehood for the indigenous tribes.

- Arunachal: A border state, Arunachal is heavily militarized and have suffered the wrath of the Chinese during the 1962 invasion. A state with the Inner Line Permit system is implemented since independence, Arunachal has strict rules prohibiting any outsiders from purchasing property, applying for jobs, and getting welfare benefits. The government’s decision to grant permanent residence certificates to a few ethnic communities living there for decades had created social unrest, leaving 3 dead and several injured during violent protests.

- Meghalaya and Sikkim: The most popular states among tourists, Meghalaya and Sikkim strictly implement the 6th schedule act that prevents any outsider to buy property in the state. While Sikkim has its unique history of accession into Indian Union, Meghalaya as the capital of erstwhile Assam State has seen its fair share of influxes, riots, and ethnic problems in the 1980s.

- Assam: As the ‘big brother’ of Northeastern states, what happens in Assam today follows across the region tomorrow. Be it the ‘Bhumiputra Aandolan’ of the 1980s, ULFA’s ‘freedom struggle’, or the citizenship issue, Assam has been the torch-bearer for the region’s political consciousness. Having suffered the onslaught of unchecked migration right from Sylhet referendum to Bangladesh Liberation War, and until this day, people in Assam are very sensitive towards issues of Land Rights, Citizenships, and external Migrations.

The point here is that the individual concerns of each state in the Northeast are paramount when it comes to local politics. The issue gets even more complex with the huge ethnic diversity within every state, village, and district. Yes, the region is lagging behind the rest of the country in terms of development and industrialization. But, at no point in history has the region voted only for development. This is a major reason why national parties do not flourish much in the region and local/regional parties are integral to any government that is formed.

It is high time that the central government learn to take off its Delhi lenses and look at the region’s problem in isolation, understand the complexities, and do not trivialize their concerns as merely a development or economic issue.

Be the first to comment on "Dear Government, All’s Not Well on the Eastern Horizons"