In Darjeeling’s case, its modern historical path is littered and pockmarked by various upheavals: Turmoil in its tea estates, language aspirations, hill autonomy to the present-day issues of full autonomy, inclusion in the 6th Schedule, recognition of all hill residents and tribal aborigines – even including Bahuns, Chettris and other Indo-Aryan Hindu caste Nepalis – as minorities.

The language’s latter-day travels to and travails as Nepali and Gorkha Bhasha in India’s Northeast, especially its explosion in Darjeeling, was recently highlighted by my ex-school teacher in Darjeeling, Mr. Ishwar Ballabh, in his weekly Simantavarti column in Kantipur [Nepali daily newspaper from Kathmandu] of Saturday, Asar 25, 2062 BS (July 9, 2005). Ishwar Ballabh, then an itinerant from Kathmandu in Darjeeling, had left our Turnbull High School sometime ago for his own life as a businessman and civil contractor, following the footsteps of the success of his famous father-in-law Mantu Lal [Chhetri].

I like to add my own personal pieces to what turned out to be an explosive period in Darjeeling’s heart, soul and soil when its intellect and sentiments were twinned to the Nepali Bhasha that united all the diverse Nepalis in the diaspora*. Conversely, this period of 1960/61 in Nepal was not one of democratic movement as in Darjeeling but a regressively repressive backtracks to imaginary demagoguery and medieval feudalism. King Mahendra had institutionalised his Partyless Panchayat Polity on the feudal foundation of the old India-based Shah-Rana-Thakuri triumvirate with Bahuns, Newars and some tribal – the latter to be gazetted as Adibasi Janajatis only in the next century – as his court jesters and sops. Whereas, as we shall see, the Nepali language movement in Darjeeling was a pan-Nepali agitation of the Nepali diaspora* in Darjeeling, and headed mostly by Matwali Nepalis with their own mother tongues, as opposed to Nepali-speaking Tagadharis (janai-wearing Hindu Nepalis), simply because every Nepali’s sole identity depended on the Nepali language.

Ballabh mentions of Nepali being labelled a language of ‘coolies’ in Old Darjeeling. From its low coolie status, Nepali had to be made ‘cool’ for educational curricula, a vehicle of overall communication and a duly recognised medium of expression in mainstream India. No less than Nepali language’s enshrinement in the Eighth Schedule of India was the agenda of the movement Ballabh, as a proximate witness from Nepal to the movement, reminisces on.

Ballabh’s early mention of Rup Narayan Sinha in his write-up is crucial. Sinha, who wrote ‘Bhramar’, the first modern novel of Darjeeling, was a handsome man in black, both as a successful and rich black-jacketed lawyer in Darjeeling’s district ‘Kutchery’ courthouse and a tuxedoed pink gin-toting Nepali Angrez Saheb at the Gymkhana and Planters’ Clubs every evening. Fair-skinned and fantabulous as Sinha was, Nepali was certainly not a coolie language for such a cool foxtrotting and fandango dancing Nepali who was an Englishman to the core. Among his many persuasions, Sinha was a pioneering writer in Nepali, and this fact lent much support to the inclusion of the Nepali Language in India even though he had passed away quite a few years ago – his funeral being the longest and biggest in Darjeeling’s memory till then.

Along with Rup Narayan Sinha, Ballabh mentions the redoubtable name of the Reverend (‘Padri’) Ganga Prasad Pradhan. Exact opposite of the colourful and flamboyant Sinha, and older by many years, Pradhan was the first Nepali Christian, a Presbyterian Pastor of the Church of Scotland, in the Northeast, to promote and propagate Nepali literacy through the translation of the Holy Bible, English hymns and psalms into Nepali, composing his own Ishai bhajans in Nepali, compiling and publishing English-Nepali dictionary and grammar, printing his religious ‘tracts’ or pamphlets, as well as formalising school textbooks in the Nepali language. His historic Gorkhe Khabar Kagat was the first daily newspaper in the Nepali language outside Nepal.

Then Ballabh suggests the Su-Dha-Pa ‘tri-ratna’ of Surya Bikram Gyawali, Dharanidhar Koirala – the latter from Nepal – and Paras Mani Pradhan, the latter living in Kalimpong, and also Shiva Kumar Rai of Kharsang who together did their utmost for the recognition of Nepali as one of the languages of India.

To their decades-old advocacy, I would add the younger names of Achchha Rai ‘Rasik’, Okiuyama Gwain, Gabriel Rana, Dr. Trilok Rai, G. Tshering while Ballabh himself mentions Indra Bahadur Rai, Ganesh Lal Subba, Agam Singh Giri and Indra Sundas of the slightly later generation while the period’s younger firebrands were Til Bikram Nembang/Bairagi Kainla (then a student from Nepal), Guman Singh Chamling, Prem Thapa, Jonathan Thapa, Tarak Bahadur Karki, Adon Rongong and others.

The demand for the due recognition of Nepali in the Indian Federal Democratic Republic was a longstanding one. But both the state government of West Bengal and the central one in Delhi seemed to air the opinion that Nepali was a bifurcated and foreign language. As for bifurcation, the Nepali leaders presented the case of Bangla in the west and north Bangal of India and also in East Pakistan, and Sindhi and Punjabi trifurcated between India and Pakistan, if not Tamil between South India and Ceylon. So what was the problem, eh? As for Nepali being a foreign language, what was the yardstick for that paradigm when Nepali was in usage for already more than a century in Darjeeling and its neighbourhoods? And the speakers of this language were the bona fide citizens of India, weren’t they?

The usual official ploy, since the British Raj days (beginning in 1907 AD), was to form commissions to arrive at something conclusive. But such august bodies practiced the usual delays and committed omissions while Darjeeling’s many polarized political leaders, especially lately, helped the official formalism by their own muteness and absence from the scene. As can be seen, the abovementioned name list supplied by Ishwar Ballabh and me has neither a single political leader nor an elected representative of any political groups, be it the Congress Party or the Communist Party or the Gorkha League of Darjeeling. The political vacuum and the active apathy of the Nepali political leaders of the region is a subject of a separate story.

[This piece was originally published in The Kathmandu Post of Sunday, August 9, 2005]

……………………

Author’s note: *Use of the word ‘diaspora’ is undesirable and inapplicable in today’s Gorkhaland, and other Nepali worlds as well, and I agree with the existential sentiment behind it.

Some minor changes (additions and deletions) have been made in this edition for Darjeeling Times/Darjeeling Chronicle.

Writes: Peter J Karthak

Kupondole, Patan, Kathmandu, Nepal

Tuesday,

This pice was originally published in TheDC FB page on – July 19, 2016. We are republishing it to help our youths connect with our history.

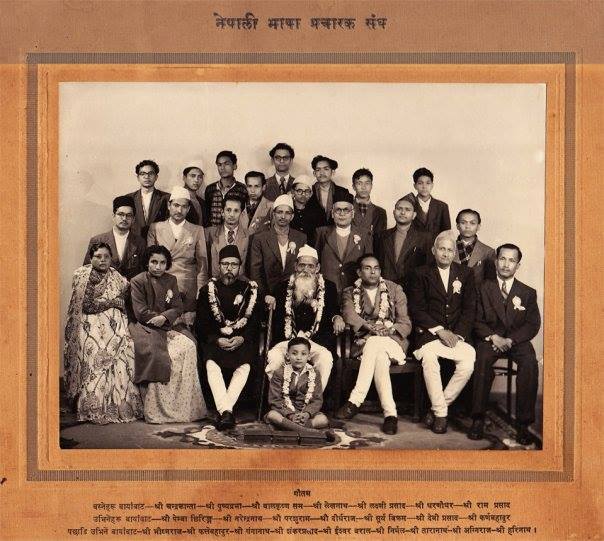

[In pic: Gathering of eminent personality of Nepali Language in Darjeeling around 1950’s includes luminaries like: Shri. Balkrishna Sam, Shri. Laxmi Prasad Devkota, Shri. Lekhnath Poudel, Shri. Dharnidhar Koirala, Shri. Surya Vikram, Shri. Ishwar Ballav amongst others]

On the language of theGorkhas ,one of the most prominent Hindi linguist Dr Bholanath Tiwari,in his book,BhasaBigyan (1987)writes” भाषाकेअर्थ मे गोर्खाली काप्रयेग नेपाली सेपुराना है। सन१९३२ मे गोर्खालीभाषीको नेपाली कहा”

DrSuniti KUMAR Chatterjee’s words” Gorkha is a nation,Nepal a state” ( ki rat ) too,clearly proves that Gorkha is the nation or what we commonly calla nation andNepali political state of Nepal.

When Mr Nar Bahadur Bhandari told Nepali reporter that mrBhandariwasaNepali and not an Indian(

that drove theNepali PM Girija Prasad Koirala to all Press conf urgently to clarify saying” mr ar Bahadur Bhandari was AN INDIAn and NOT a Nepali.He even went a step further and told” had mr Nar Bahadur Bhandari not been an Indian,he could not have been the CM of anIndian state of Sikkim”

Nepali term should not have been included in the Indian Constitution as this has made Indian Gorkhas not only Trishanku but the process has put us back to 1971

SubhasGhising’s plea for Gorkhabhasa in lieu ofNepali would have been far more meaningful for us.last36 years experience has proven that