This particular story’s fodder is provided by something peculiarly provocative that happened in Darjeeling that Ishwar Ballabh wrote in his aforementioned Kantipur column.

That the Government College of Darjeeling decided to drop the Nepali curriculum from its collegiate studies, and this ‘decision without consultation’ helped add combustible woodpile to the already tinder-dry situation in the Northeast. Without the Nepali language, the Indian Nepalis had no identity: It was as simple as that. Therefore, there was no alternative to spoiling for a fight.

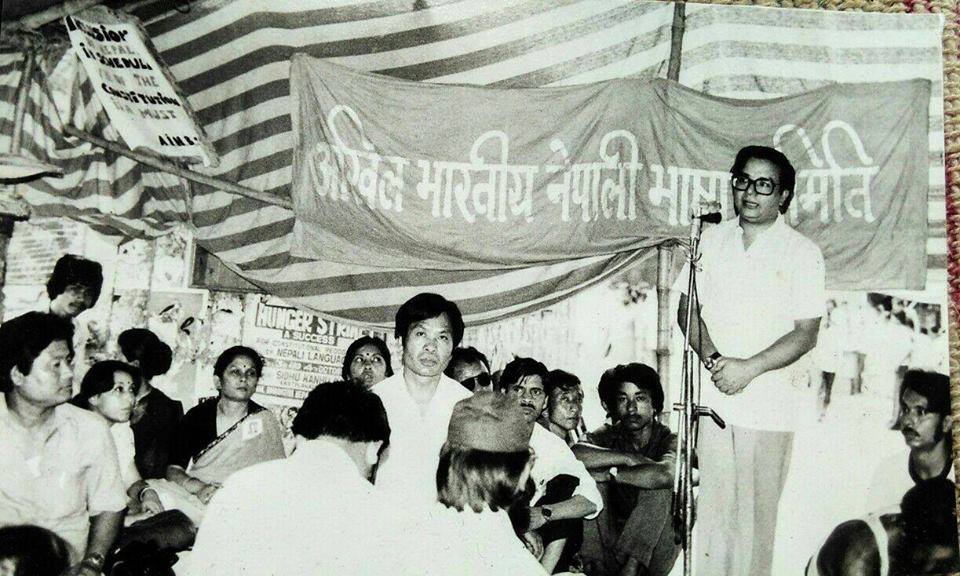

It was at this very juncture the apolitical personalities of Ganesh Lal Subba, Indra Bahadur Rai, Indra Sundas and Til Bikram Nembang – the latter a Government College student from Nepal – emerged as a knights’ quartet to spearhead the language campaign. What had started as a pocket of student protest turned into a mass movement, and day by day the agitation spread like wildfire and assumed a pan-Darjeeling revolution in which all the bustis, tea estates, cantonments, satellite towns and urban areas joined in, and thus the total transfer of a local protest to a mass action was accomplished.

It was the time when I was at the threshold of my school-leaving period and the expectant entry into collegian life. Darjeeling had seen the arrival of Governor Padmaja Naidu, the daughter of Sarojini Naidu, to take up her summer residence in Darjeeling. I remember the final days at Turnbull High School when Indra Bahadur Rai, our teacher of Nepali, reported to us:

‘Boys, our delegation met the roly-poly Governor inside the Raj Bhawan and we presented our case point by point. The fat woman rolled on the sofa; we did the same. She belched, and we also returned the favour in our own ways.’ It was a rare instance of gentle IB Sir angrily parodying a power-that-be, the executive agent of the central government in the state. We laughed.

Nothing came out of the many meetings with the Governor. The situation worsened by the day. Next was the Chief Minister of West Bengal Dr Bidhan Chandra (BC) Roy’s turn to visit, ostensibly to pay his courtesy call on the Governor in the summer capital of Darjeeling and to settle the language issue as well. But it was a foregone conclusion in the minds of the populace: Nothing concrete would emerge; it was all a sham, a mere formality at dialoguing. Let it boil, simmer and it’ll settle down and fade away on its own eventually. That was both the state and central view.

Indra Bahadur Rai would have none of it. From the public podium of Chowk Bazaar, he bellowed from his pulpit like never before:

‘Let him [tyo in Nepali] come and let’s welcome him [tyaslai] with closed doors and windows and shuttered shops. Let there be no traffic, no vehicles, no people in the streets tomorrow. Tyasle will see a wasteland here and will go from a cemetery. Let’s give tyaslai this kind of reception.’

The town erupted in unanimous agreement.

Next was the turn of Amber Gurung and his Art Academy of Music ensemble, of which I was but a junior member. He played his harmonium and sang his composition to Agam Singh Giri’s anthem, ‘Sugauli sandhi hamile birseka chhainou bhanideu/Tyo Killa Kangra hamile bhuleka chhainou bhanideu.’ Accompanying him were Rudra Mani Gurung, Shekhar Dixit, Saran Pradhan, Ranjit Gazmer, Aruna Lama, Karma Yonzon, Gopal Yonzon, Jitendra Bardewa, Lalit Tamang and other members of the Academy, playing their instruments and supporting Amber’s principal voice with chorus lines and refrains. The music charged the crowd further that afternoon.

On his part, Ganesh Lal Subba, the dapper lawyer, recited many stanzas from his English translation of Laxmi Prasad Devkota’s ‘Muna Madan’ following the fiery speech delivered by Indra Bahadur Rai. Subba’s literary rendition and Amber Gurung’s music were broadcast that afternoon as part and parcel of the Nepali heart and soul in Darjeeling.

Indeed, Darjeeling was a ghost town for the veteran doctor politician BC Roy, the Chief Minister of West Bengal, who was welcomed with exclusion and was packed off to his Coventry in Calcutta with ridicule. The Darjeeling debacle remained unresolved. Even the jamdar or Harijan sweepers and cleaners of the town downed their brooms and buckets. The streets remained empty of people and littered with uncollected garbage, shops and houses closed, schools and offices locked up, and the state’s chief executive’s motorcade received the confetti of flying newspapers along the deserted routes. The impasse with both Governor Naidu and Chief Minister Roy was fast in place, with no compromise in sight.

In three volatile days, the Nepali Language gauntlet picked up by the students of Darjeeling Government College was handed over to the general public and it became a mass movement. The law and order situation deteriorated rapidly. The local constabulary force of WBP (West Bengal Police) was inadequate, and the nearby Bloomfield-based WBAP (West Bengal Armed Police) were put on alert. But both forces, being manned by local Nepalis, were not keen to shoot at fellow Nepalis. The next alternative was to call in the State Reserve Police Force (SRPF) and the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), mostly with plains Indians in the two paramilitary formations. But they were so far away, spread and stretched thin in other troubled spots of the far Northeast.

In such a civil war situation, an unprecedented development was allegedly taking place behind our backs, in secret. This was the decision to mobilise the Indian Army itself, and this came in the form of assigning the unpleasant task to the 2/8GR (Gorkha Rifles) stationed in the nearby Lebong Cantonment, hardly 20 kilometres away from town. If this were true, it would be the first case of the government resorting to its military to quell a civil agitation that simply demanded a just address through dialogue and negotiation for settlement.

As was routine in the armed forces, various infantry regiments in rotation of three years each visited the Lebong Garrison. The 2/8 Gorkha Rifles were in residence for some time, and its crack football team was a fact to reckon with in soccer-crazy Darjeeling.

Published in The Kathmandu Post of Sunday, August 14, 2005

………………………..

This is the 2nd part of a 3 part series on Nepali Bhasa Andolan, the 1st part was published yesterday [you can read it here: https://bit.ly/2PktDLl] written by one of our eminent contemporary writers Mr Peter J Karthak. we request all of you to kindly SHARE these articles, so that it reaches all of our people, and make them aware of why conserving our language and heritage is so important. We THANK Mr Karthak for kindly permitting us to reproduce his work.

………………………..

Author’s note: Some minor changes (additions and deletions) have been made in this edition for Darjeeling Times/Darjeeling Chronicle.

Writes: Peter J Karthak

Kupondole, Patan, Kathmandu, Nepal

Tuesday, July 19, 2016

This piece was originally published in TheDC FB page on – August 21, 2016. We are republishing it to help our youths connect with our history.

Leave a comment