Growing up in Darjeeling, Ram was never one of the important Gods. Shiva and Durga held complete sway, as they continue to do till date.

We read about Ram in ‘Amar Chitra Katha’ or ‘Wisdom’, as kids, where his name was always written as ‘Lord Rama’.

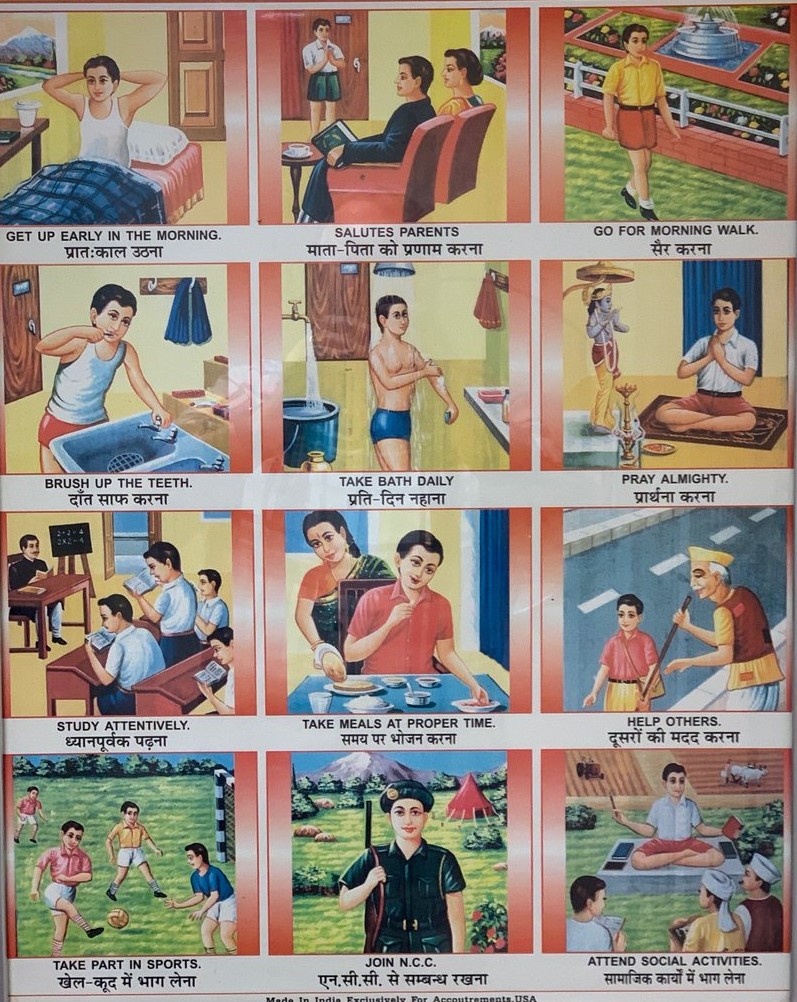

Amar Chitra Katha portrayed him as the perfect son, which may have given rise to one of the first sentences we learnt in our English language books – Ram is a good boy. The accompanying illustration to this sentence was of a ‘North Indian’ looking boy, hair neatly combed, wearing shorts and smartly tucked in half sleeves shirt, performing ‘good boy’ deeds.

So both Bhagwan Ram and good boy Ram were too remote from our lived experiences.

There were, of course, old calendars with images of Ram, Sita, Laxman, and a kneeling Hanuman in our puja rooms/corners. Important or not, our grandparents would never dream of throwing away calendars with images of Gods, even though the material world impinged in the form of ‘Shri Laxmi Traders, Hill Cart Road, Siliguri’ written right below the kneeling Hanuman.

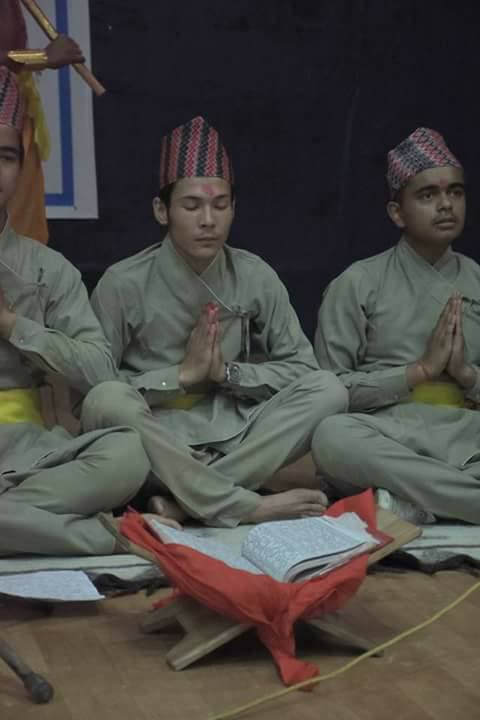

As we grew older and reached middle school we could have come closer to Bhagwan Ram, but that wasn’t meant to be. The occasion of Bhanu Jayanti, the birthday of poet Bhanu Bhakta Acharya could have given us a perfect platform. Bhanu Jayanti was always celebrated by chanting excerpts from the Ramayana, with a framed photo of Bhanu Bhakta garlanded with a floral mala, (the convenient and recyclable khada was yet to be popularized).

Bored students would chant indifferently, passages of Bhanu Bhakta’s Ramayan. The Nepali teacher who throughout the year was a marginal figure in the school suddenly rose to the occasion and took charge.

For a fortnight preceding the event, s/he would try hard to instil awe and reverence among the students, so that they understood the significance of text in our cultural history. But of course, students’ lives have more critical issues than Nepali bhasha ko utpatti (origin and development of the Nepali language), so they couldn’t be coaxed into putting an iota of emotion in their recitation.

At the end of the programme, the teacher would take the red cloth-bound Ramayan and the framed picture of Bhanu Bhakta home, to be revived again after a year. So I think if you were also like me, you too only remember the first one and a half lines of the Ramayan:

“Ek din Narad satya log pugi gayaa/

Lok ko garaun hita bhani…“

That’s all. So even Bhanu Bhakta failed to bring Ram from the margins and it was the story of the Ghansi, the grass cutter, that we remembered.

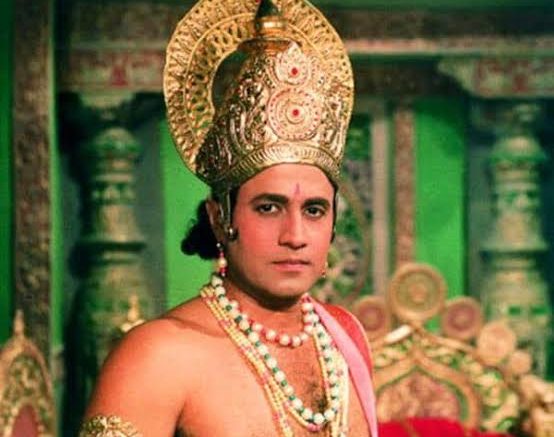

Ramayan later captivated us when Ramananda Sagar’s magnum opus became a Sunday morning ritual across the country. In Darjeeling, instead of raising the hierarchy of Ram in the pantheon of Gods , the serial’s main contribution was to help increase the vocabulary of the elders. Pre Ramayan we had one word, “Bhagyamaani”, post-Ramayan there were many choices- Ayushmaan Bhava, Chiranjeevi Bhava, Saubhagyavati Bhava, among others.

Even the growing popularity of Sai Baba of Puttaparthi in Darjeeling, whose followers greet each other with ” Sai Ram“, failed to mainstream Bhagwan Ram. Hence it was not surprising that the unfortunate Babri Masjid incident, one of Rajiv Gandhi’s missteps, did not evoke strong reactions in the hills.

Therefore it’s fascinating that Ram has suddenly catapulted into prominence. When a Tenzing Bhutia or a Samuel Lepcha writes ‘Jai Shri Ram’ in social media, you know Ram is no longer only a deity.

On seeing that chants of ‘Jai Shri Ram’ infuriates Mamata Banerjee, Darjeeling with its inherently syncretic and subversive culture has taken ‘Jai Shri Ram’ and made it it’s own. Jai Shri Ram has now metamorphosed into a show of dissent against the Bengal government, rather than simple praise of a deity.

And this can happen only in Darjeeling.

[Writes: Divya Pradhan, she is an Asst Professor of Literature at Delhi University]

Be the first to comment on "Ram in Darjeeling"