If ever there was a point in our past that changed the fabric of our entire community, I would have to flip the calendar to lay a finger on Sunday, the 27th of July, 1986. Indeed, that is a day that will go down in the annals of Kalimpong and Gorkhaland history as “Our” Black Sunday.

It is a day that continues to live in infamy, for in that tragic moment we all turned a corner and underwent a complete transformation. Quite unknowingly we bid farewell to our in-borne innocence and inherited, what some have quite candidly labelled as, the “Inheritance of Loss”. We undoubtedly inherited a great loss, the burden of which we carry to this day.

It did not all start out that way, or rather no one had quite envisioned the tragedy and atrocity that that day would bring upon us.

It was a bright, hot summer day in late July. The Gorkhaland agitation—the demand for a separate state for thousands of Nepalese living in Darjeeling, Kalimpong and its sub-division – had gripped the hills. Every man, woman and child’s interest and involvement in the agitation was adequately piqued. The movement undoubtedly had reached a feverous pitch. Darjeelingeys brimmed with fervour towards the cause and supported it with a dedication that almost equalled blind faith. A burning passion for the land had kindled the heart of every darjeelingey, and every lip pledged support to give their life if need be for “our maato”.

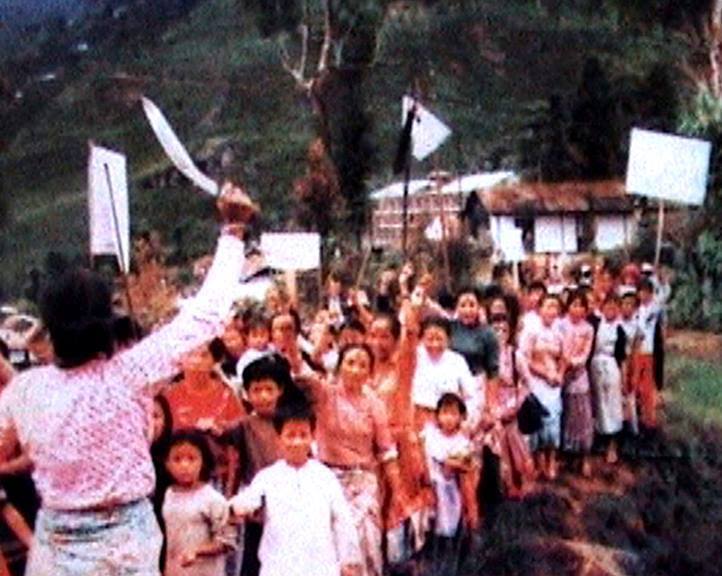

On 27th of July, 1986, I woke up to the murmurings of an entire village drenched in a carnivalesque mood. Women draped in colourful chowbandi cholos paced the streets with saipatri malas hanging around their neck. Men in daura suruwals and khukuris slung by their sides walked alongside, eager to impress their female counterparts. Every other person, musically challenged or not, sported a beat or two on the madal. Festoons fluttered in the afternoon breeze and shouts of “Jai Gorkha-Jai Gorkhaland” pierced through the ravines and cliffs. On that day, cultural, societal, economic and religious boundaries seemed to fade and had merged as one. Everyone, be it bahun, rai, limbu, kami or damai spoke with ONE voice, with one purpose, such as, or had never been seen before.

At the heart of all the festivities was a much somber issue. The Indo-Nepal treaty which in a way had sealed the fate of the Nepalese and their status quo in India lay at the heart of this contentious issue. Shrouded in uncertainty, Clause 7 of the treaty came to be synonymous with the ambiguous legal status of the Nepalese living, not only in the Darjeeling, Kalimpong Hills but throughout India. Our “Identity” as legal residents of India was in itself brought to question. A mass campaign was therefore organized, to burn the flags of the two countries and to nullify the treaty. Leaders at the local level had planned a non-violent march to the main town square to make their demands heard. It came as a step in the direction to gain an equal footing as rightful, legal, tax-paying citizens of India.

All the hills, from children to adults, from men to women all cried out “I rebellion “WE WANT GORKHALAND”

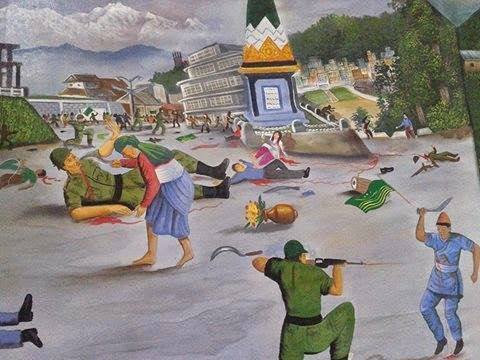

As expected there was a huge turn-out. Processions from all quarters of town with its share of musicians, dancers, men, women and children converged at the main town square roughly around mid-day. But just as they were approaching the police head-quarters someone heard a loud boom. Unaware of what was going on, the crowd continued under the impression the sound was from a firecracker. Then the boom was followed by yet another, then another and yet another loud boom. No one quite knew what was going on, but commotion broke loose as a lady fell to the ground with blood streaming down her temples. As the realization of a cruel reality slowly filtered in, mass hysteria ensued.

Armed forces, unbeknownst to the crowd had crept atop buildings along the road and were firing blindly, mercilessly and ruthlessly at the unarmed crowd below. Women scurried to protect their young ones from flying bullets. Children ran aimlessly even as their fathers were shot down like animals on a firing range. Mothers saw their sons falling by their side, children witnessed blood streaming down the cheeks of their parents. The elderly lay dying by the street, struggling to let go of their last breath. Men attempted to combat the oppressors with bare essentials but to no avail. Every shot fired from a vantage spot gave birth to an orphan or to a widow. In the end, cries for a loved one, cries of loss and cries of pain were drowned among a heap of bodies that lay strewn along the road and hill slopes. Gold ear-rings lay unclaimed by the gutter, sarees lay drenched in blood, a stray pair of sandals lay by the roadside even as its owner lay face down against the hot, hard and rough surface of a blood-stained road. After what seemed like hours of massacre, all that remained were remnants of life or lives that once was, or once could be. Deathly silence crept upon the land, as confusion gave way to mourning. It was a horrid spectacle reminiscent of a scene out of the Crimean war.

The Law of the land or rather the lawlessness behind the action towered above the din of death. Surely no law or an attempt for its justification could legitimize a gruesome act of this magnitude. Our Human rights had been violated. Our Constitutional rights had been violated and ceased from us, but alas who was there to speak for the dead, or rather, who among the living could testify against this gross injustice. Celebration turned to lamentation, laughter to tears and hope to hopelessness. Kalimpong and her children had been murdered, yet, who was there to grieve for the dead or console the living? It was a dark, a very dark period in our lives. Indeed, the cries of the innocent reverberate, to this day, in the streets and in the building alleys.

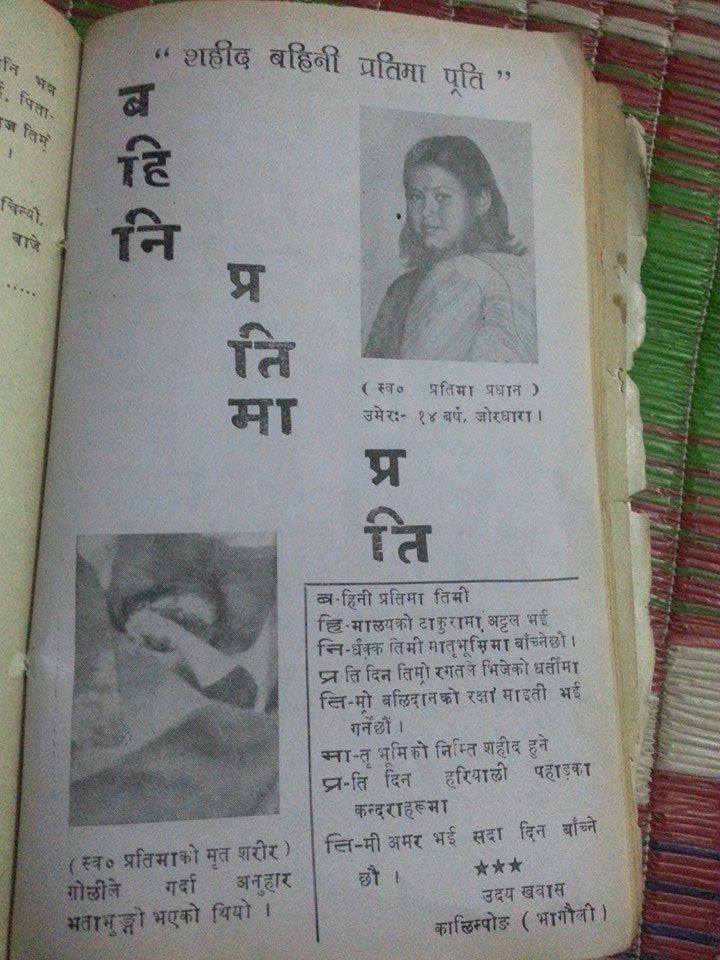

14-year-old Pratima Pradhan from Joredhara, whose face was shot beyond recognition that day. What was her mistake?

Many years have passed since Kalimpong first tasted the bitterness of death. Many years have passed since that fateful day in July when we lost so many of our loved ones to gross injustice. Many years have passed since that black Sunday, yet memories of their painful death stare upon us like an open wound. We have shed many tears since; we have buried many loved ones since, and continue to grapple with the pain inflicted upon us.

Politics and politicians have inevitably forgotten or rather, have chosen to forget the trail of tears that the people have shed. They remain true to their fabric, choosing rather pursue interests that fuel their individual pursuit of fame and fortune.

A massacre of a different kind now looms large amidst us. It is now up to us to remember the price we paid to gain what was rightfully ours. It is up to us to cherish and respect the life and death of those who we once lost. It is up to Kalimpong and her people, to remember and hold onto the hope that was once alive.

Just as the soul of every martyr remains aflame within the pages of our history, so too “Our Story” remains immortal in our psyche: Our Story is worth the memories!

Writes: Janice Mukhia

Leave a comment