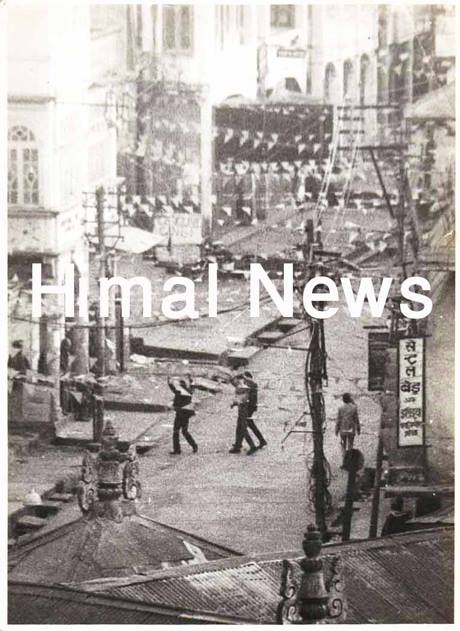

In 2014, we had started a Special Series on Gorkhaland Andolan, wherein we had sought to document the lived history of our people from the 1986-88 andolan days and beyond. After we did a few stories, the series had remained dormant, till we received the following article by our contributor Divya Pradhan*. We request all our readers who have lived through this period to kindly contribute your experiences. This is our lived history, and if we do not document it, no one else will.

Nabin Fell Down and Broke His Crown

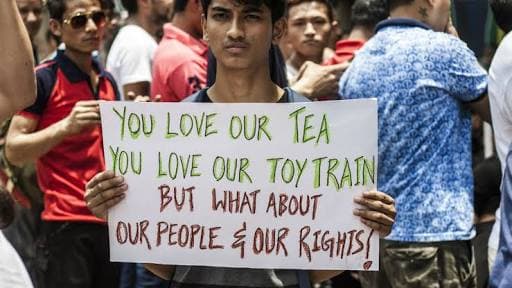

The collective un/conscious of the Indian Gorkhas, is a storehouse of memories, some are lost to history, some lie buried literally and metaphorically, but most of it remains, simply hidden behind a veneer of the quotidian, coming to haunt us every time we are under attack. What else would explain our doggedness in the face of state sponsored tyranny, failed leaderships, and pliable accomplices from among our own? Why do we come together every time we hear the word “Gorkhaland”? Why do we carry this historical burden in our psyche? And importantly, in spite of our tenacity and sacrifice, why do we fail? It’s easy to blame leadership, the ecosystem around the particular leadership or a tyrannical state but at some point in time we have to introspect, and ask fundamental questions like- What is my individual contribution to the movement? If our demand is being compromised, what have I done to stop it or at least mitigate the effects? Barack Obama once talked about the woke generation and how they should know that, social media activism is not the same as participating in a real movement. Is that where our fault lies?

“Come as you are, as you were

As I want you to be

As a friend, as a friend

As an old enemy”

-Kurt Cobain It was going to be just another day of eating, reading and road-badminton. With schools closed again, we have been bundled-off to our grandparents’ house in Phuguri. We love it here and everyone adores us. It is our mawali after all. All the elders of the village call us by our pet names and asks, “Aayis? Kailay aako?” This is always accompanied by appreciative and loving comments on how much we have grown, since the last time they saw us (not more than three months ago).

Like us, our cousins have also come back and it’s just like dasain, but not quite.

The anxiety in the air is palpable, especially since terror has come closer home. We are too young to comprehend the gravity of the situation, but my cousins who are only a couple of years younger to me have a dejected look on their face. Their father, my uncle, is in hiding. A close aide and nephew of Ghising, he is a wanted man. “Wanted” is such a loaded word, conjuring images of tough criminals, but Gyanen mama is a softie, someone who can always be depended upon to buy us dalmut and lal patthar from Modi ko dokan. It’s been weeks since he left home along with other men and no one has heard from them. The very absence of news from the missing men must have been a source of consolation for the families.

There are hardly any men around, there are some “CPM” men of course. CPM for us kids meant those whose fathers were at home and there were others who were not-CPM like Nipen, whose father was missing. However we aren’t particularly interested or disturbed by all this. Shops are closed, schools are closed and we are in Phuguri in the middle of the academic session, and we couldn’t care for anything else. Today too, we plan to play badminton on the main road in front our house. It’s a clear day, blinding blue skies with tufts of cirrus clouds, against the backdrop of emerald tea garden bushes. We can see as far as Sonada and Kurseong and the awe-inspiring ambattay ko pairo.

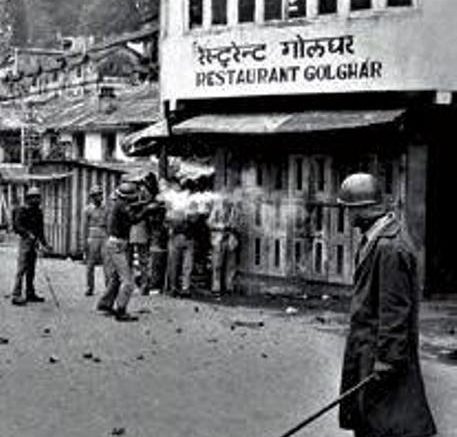

My cousin-uncle, Niraj mama is also my dauntari, he always lets me stand on the leeward side so that I have an advantage over him while playing badminton. We play on the mainroad , so it’s always windy. A convoy of CRPF truck trundles by so we have to stop our game, which I am winning, because of my opponent’s generosity. Immediately after a few minutes, we hear a shot ringing and women rush out from their homes.

Nobody knows what happened. A couple of women standing outside say that they heard the shot coming from Tingling fatak, they say they saw someone fall down. Minutes later, we hear that Nabin who was sitting on the culvert near Tinglink fatak ko hawaghar was shot, pointblank.

I didn’t see him fall; I didn’t know who he was, I only remember these words – “Nabin” “culvert” “Purlukkai” “herda-herdaii”.

I have no memory of what happened after, but the word ‘nabin’ always takes me back to that day- n-a-b-i-n, not navin but nabin.

…While writing this, I spoke to my uncle about the incident and he told me that the man who was shot was Robin a handy boy of a local bus, and not Nabin. Somehow Nabin conjures images of Jack who fell down and Jill who broke her crown and came tumbling down…

[Writes: Divya Pradhan, she is an Asst Professor in the Department of English, Mata Sundri College, Univeristy of Delhi]

Today only I read both part, I & II and which takes me back to Gangtok, where I was working in those days. My colleagues who’re from Darj Kalimpong used to tell us what they saw. Every household had one or more guests from Darj, Kalimpong or Duars. I have some stray experience of NJP to Calcutta during 1988.